[From a short analysis of the ways in which our bodies can be related to a thing, the reason we have five, and not four or six, senses becomes apparent. Put another way, this is a terrible summation of Aristotle's discussion of the senses in his "On the Soul".]

Given that a person is a mind and body united as a composite whole, based on the previous post, we would need to bring in something to think about, if all the mind is is "empty equipment". I don't think we entirely lack innate ideas, but I also think we only get our ideas by means of sense experience--how the two can be held true at the same time without contradiction is something I will get into in another post, maybe even the next one!

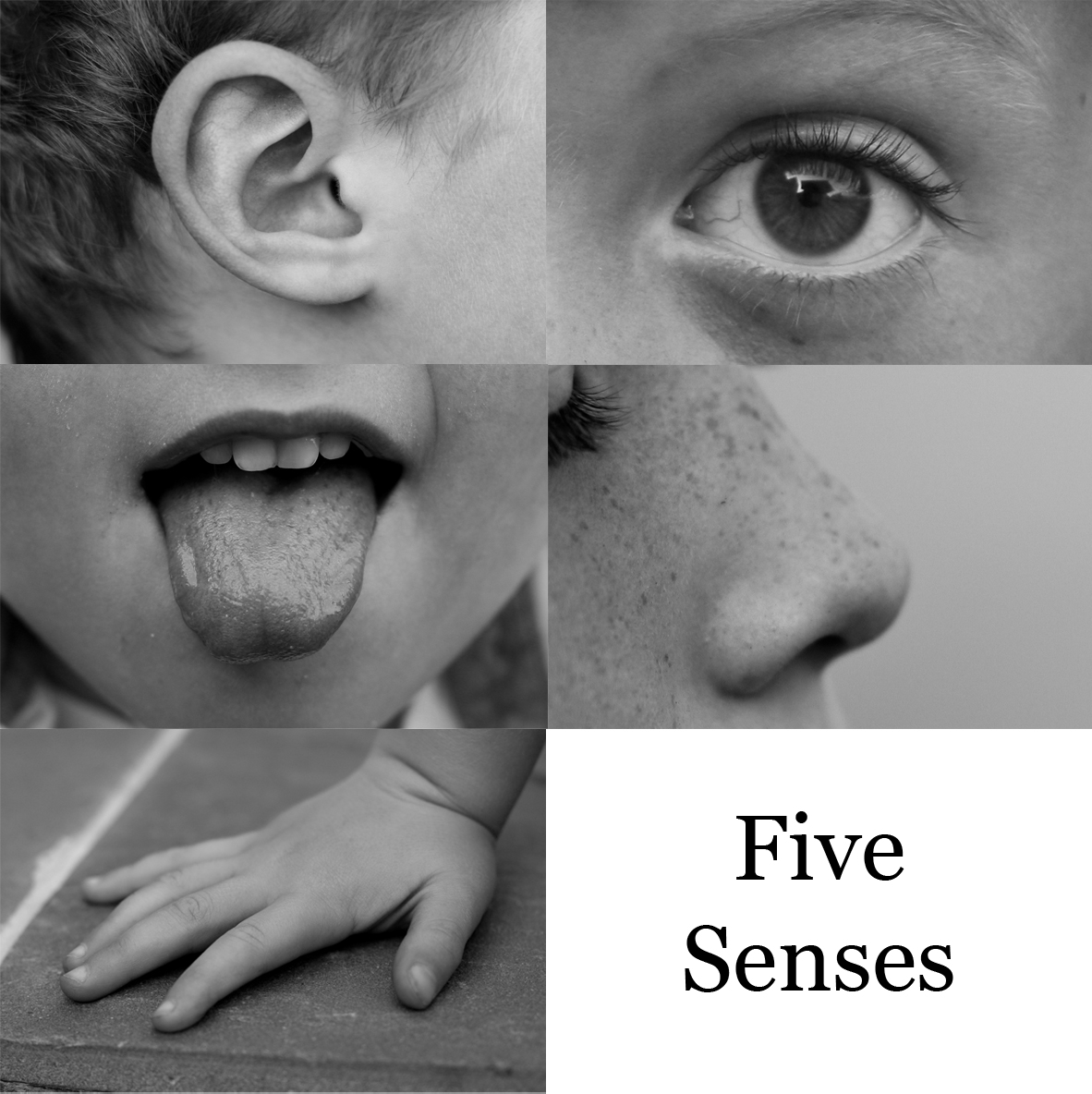

So if we are embodied minds or ensouled bodies, then we would have to have some kind of mechanism for getting the world around us into us. Or rather, instead of saying, "would have to," it's simply a matter of, "it seems manifestly that we do". These mechanisms we call the senses. (We are focusing entirely on the senses which are *external* to the body for now.)

Since we are bodies, we could relate to the other bodies/things in a few important ways. The most important way we could relate to an object is spatially, as material objects are defined by their being spatial. Descartes seems to be right here, that mind is thinking-stuff and matter is spatial-stuff, even if his understanding was skewed by his method.

Spatially, the most immediate relation is, given that no two objects can occupy the same space at the same time and be distinct objects, adjacency. Either we are right next to the thing, or we are not.

Further, if something is going to come into us somehow, it has to affect us in some way. It can either do it directly itself, or it can affect something else, which is the actual thing we perceive, but based on which we know the object producing the effect exists. This doesn't count the body, since it's a part of us, even though it is affected, and then it comes into the mind where we fully perceive the sensation.

So a thing that's adjacent to us and affects us directly by its space is sensed through touch. Since the object is touching us itself, we can also discern some other qualities about it based on the way that moving whatever is touching the object over that object is resisted or easy (whether it's rough or smooth), and things like that.

Something adjacent to us, but acting indirectly, that is, through a medium, is sensed by taste. Taste is like touch, and is one of the most basic senses. That might have something to do with why babies constantly put things in their mouths! Taste is specific, though, because while touch tells us that there is an object, and few other things, without which we would easily die, and moving around would be seemingly impossible, taste has to do with eating. Once we find something, via touch, we have to tell if it is sustenance or not. Since we are made of chemicals in a precise balance, as far as the body goes, taste relates chemical information to us.

If a thing is not adjacent to us, but is acting on us itself, we experience that as smell. As unappealing as it is, nasty smells are little pieces of the thing coming to us. Thankfully, a good whiff of muffins or bacon also contains little muffin or bacon bits, too! This is a lot like taste, in that it gives us chemical information, since it, too, has to take in bits of the thing. This is also why smell and taste are in specific organs, rather than all over like touch--because the senses have to take some little piece in of what is being sensed directly, even though as a whole it serves as a less-than-totally-direct sensation, and because some things are harmful to take in. The immediacy of smell and taste make them similar in manifestation, and they are also similar to touch because they sense something as a piece itself, though they sense the whole indirectly.

Something not adjacent to us, and acting on us through a medium can do so in two ways. Since touch and taste involve sensing the object adjacently, the object itself must be doing the acting. And since both touch and smell are sensation of the object itself, similarly the object must be the active thing. But now that we're looking at things that aren't touching us and are not directly affecting us, it could be that the thing is the actor, or that it is not the cause of the action that we sense. Our senses have to have an actor causing them, since the whole idea of a sense is something coming into us. Maybe we could shoot beams of light from our foreheads to see with, but sight would not be in the light-shooting, but in taking in the light shot out bouncing to our eyes. Sensation is one-way, even if perception may not be.

So something not adjacent, acting through a medium, and active itself will produce an effect on the medium that comes to us, and this is what we call sound. All senses sense change. We don't really think about what our fingers feel like unless something changes--like slamming them in a door. We don't really think about what our mouth tastes like unless some flavor changes it. So if the effect on the medium changes, it will involve the passage of time. Time doesn't really get associated so much with taste or touch or smell, but with hearing the pairing is obvious--music is entirely based on this connection. The most abundant medium is air, so unless underwater, this is what fills our ears. And since the air surrounds us, and usually the object in all directions, in order to sense a particular object more specifically, we have directional senses like our ears, which focus the sensation.

Finally, something not adjacent, acting in a medium, and being acted on itself by something else is sensed as sight. Since the thing is being acted on, and the most abundant actor in nature is light, we sense the light acting on the object. What is the medium? Well, one could either say the water of the eye before it reaches the sensor itself, perhaps used to further the contrast with the air in hearing (and there are things like insects and simple-eyed creatures that don't have this feature), or something like the aether which was held to exist until the Michelson-Morley experiment of the early 1900s, and which I think could be the pilot-wave in Bohmian quantum theory.

Honestly I am going to stop there with regard to the senses. Looking over Aristotle's work again, and the Scholastic expositions of it have really left me feeling humbled by the completeness of their approach, at least vastly with respect to this little article.

The main idea was to establish that a thing can either be adjacent or not, in a medium or not, and either active or being acted upon, and the sum of the real possibilities of those three divisions results in five sensory faculties, matching our lived experience, provided someone is not blind or deaf or things like that.

Why red looks as it does, or why saltiness tastes like it does is far beyond me, and I know of few people who have stepped into waters that deep. Maybe someday I'll be able to grasp such a thing, but for now, it is out of my reach.

That's alright, though; the wonder drives philosophy and inquiry on.

No comments:

Post a Comment